Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know

Or Extraordinary How Potent Cheap Fiction Is

Tall.

Dark.

Handsome.

That could describe either the motorcycles or the men who ride them. Or both. For the male motorcyclist has become the hot new hunk of romance novels.

Over the past ten years, there have been between three and four thousand romance novels with a biker as the hero. (In romance novels, we still have heroes and heroines.) That’s more than the total number of motorcycle adventure travel books published in the last one hundred years.

“Romances with motorcycle clubs and/or heroes who ride motorcycles have increased in popularity in the past few years, and TV shows like Sons of Anarchy can take some of the credit for that,” said Erin Fry, a spokesperson for the Romance Writers of America (RWA), a professional organization with more than ten thousand members. “Often romance novels reflect popular culture, so it’s not surprising to me that romances with motorcycle heroes/heroines are popular”.

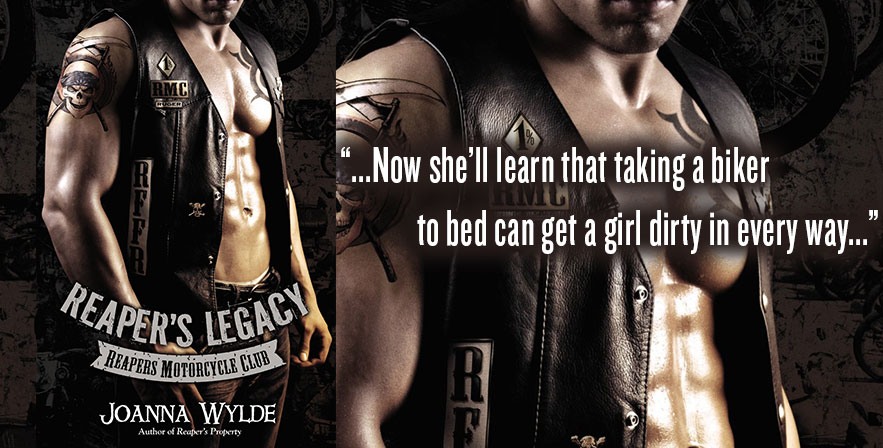

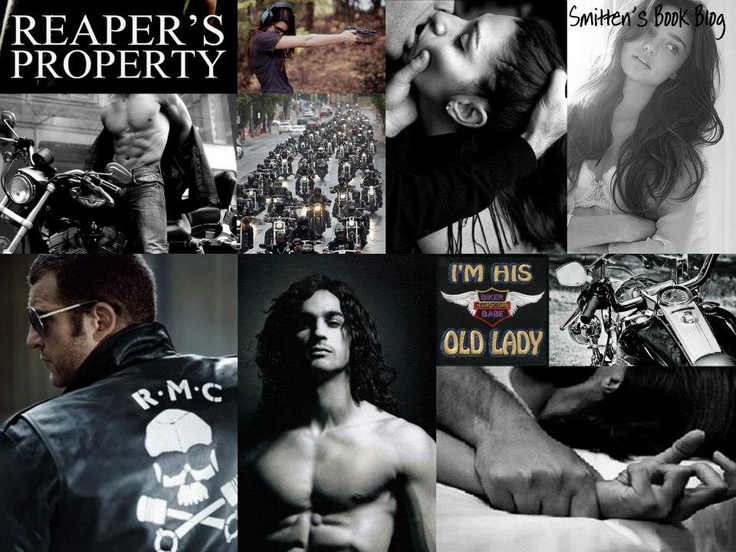

Joanna Wylde, who is known for her best-selling Reapers MC romance novel series, is among those who were inspired by Jax Teller and the gang. “Sons of Anarchy got me started on my research. I caught an episode completely at random. What caught my attention was the club’s formal organizational structure. I thought it was ridiculous. In my mind, MCs were just chaotic gangs. I started researching, thinking the research would back up my preconceptions. Instead, it opened my eyes to a whole new world.”

For Jessica Moro, writing in the Heroes and Heartbreakers blog, it may be less the club and more the clubman. “Jax Teller is the epitome of the MC hero: tough as nails attitude, loyal, caring, and hoooooottttt. MC books have become quite the rage and it seems this type of hero won’t be fading away any time soon. What makes a great MC hero? Tough love, alphastastic attitude, a deep loyalty for their brothers, and they’re incredibly sexy!”

Katie Ashley was not only inspired by Teller and Sons of Anarchy, she also dedicated her book, Vicious Cycle, to Charlie Hunnam, who played Teller in the TV series.

It’s easy to laugh at genre fiction, the proverbial “cheap fiction” of yore, until we look at the numbers. Here is the States, romance novels are a billion-dollar-a-year industry with more than 10,000 new titles appearing annually. It is the second most popular category of fiction after ‘general’, 17% and 27% respectively. Not that Britain is a slouch when it comes to romance, Victoria Wood’s Barry and Freda notwithstanding. According to the statistics provided on the Romance Novelists Association (RNA) website, the British consume 24 million romance novels a year, adding up to more than a hefty £118 million. Not only do more people read general and romance fiction in Britain, but also the gap is smaller: 26% for the former v 22% for the latter. In raw numbers, that’s about 5.6 million, as opposed to the 4.7 million who bought crime/mystery or the 4.5 million who bought adventure/thriller. No wonder Rupert Murdoch’s NewsCorp bought Harlequin for $415 million dollars a couple of years ago.

Yet genre fiction never quite gets the respect it deserves. When I was in university in the 1970s, genre fiction was still seen as second rate or ‘cheap’. Only crime got some respect (and regular reviews in the all-important New York Times) in those days. While some of the other genres were receiving critical attention, it was not considered real culture (or high art). Its importance, or potency, was beginning to be addressed, but it was slow and often with the sort of self-mocking dismissal in the mangled Noel Coward quote from Private Lives that I used as the sub-head. Ironically, romance, arguably the first recognizable genre in the English language, may be the last to gain any respect. Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740) is not only the first novel in British literature, but also the first romance novel.

But it’s been a while since virtue was rewarded. Nowadays, in romance novels the virtue is easy and the rewards motorcyclic. Is it still what we all think of when we say “romance novel” or it is something else? Come to think of it, what is a romance novel?

The RWA states that a romance novel has two basic element: a central love story, by which it means the main plot centers around people falling in love and trying to make the relationship work; and an emotionally upbeat and satisfying ending, the just reward for the risks for each other and their relationship.

The RWA states that a romance novel has two basic element: a central love story, by which it means the main plot centers around people falling in love and trying to make the relationship work; and an emotionally upbeat and satisfying ending, the just reward for the risks for each other and their relationship.

The RNA rejects this definition without replacing it with one of its own. The examples it gives seems to indicate that the RNA includes all of women’s fiction – which means it includes other sorts of relationships and individual titles may exclude romance altogether. The statistics it supplies however seems to suggest that there is a narrower definition at play somewhere. Pamela Regis, in A Natural History of the Romance Novel, defines romance more specifically and recognizably: “a work of prose fiction that tells the story of the courtship and betrothal of one or more heroines”.

The RWA adds to its definition, “Beyond that, however, romance novels may have any tone or style, be set in any place or time, and have varying levels of sensuality. Romance fiction may be classified into various sub-genres depending on setting and plot elements.” Sub-genres include contemporary, erotic, historical, paranormal, suspense, comedy and young adult.

However, the sub-genres (or genre hybrids) don’t change the essential definition. Billy Mernit, who produced a book called Writing the Romantic Comedy, defines the sub-genre: “a romantic comedy is a comedy where a central plot is embodied in a romantic relationship”. In romantic suspense, which is more plot than character driven, the process of solving the mystery or defeating the villain helps define the characters to each other and helps them fall in love. According to Regis, Mary Stewart, better known these days for her Arthurian series, is “the mother of twentieth-century romantic suspense” because the two elements are “organic” and “seamlessly integrated”.

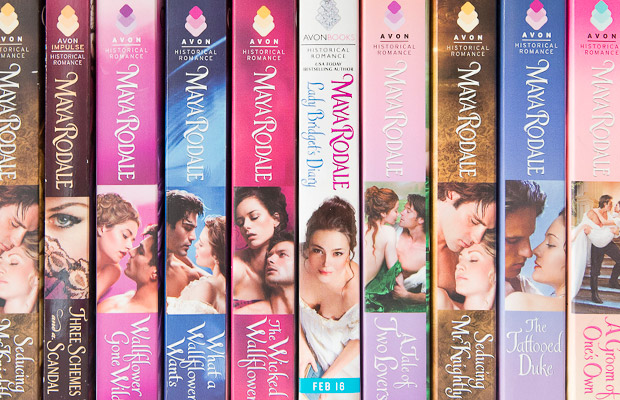

Interestingly, romantic suspense is also the most popular sub-genre. The RWA puts it at 53% of the market, while Maya Rodale in Dangerous Books for Girls puts it at 67%. It is also the sub-genre in which most, if not all, MC romance novels fall. This is speculation on my part since there seem to be no studies on the subject, but it may be the sub-genre which accounts for the bulk of the 16% of the male readership of romance novels in the U.S. In the UK, it’s 22%. “I think (based on my anecdotal experiences) that motorcycle club romances are more popular with men than the average romance novel,” Wylde said. “They seem to see it as an action adventure.”

Genre is made of narrative elements. We can’t have a murder mystery without a murder near the beginning and a scene exposing the murderer at the end. In our own sub-genre of motorcycle adventure travel we need, in addition to a motorcycle, encounters with several interesting people and a few set pieces, usually, by not always, pitting the rider against nature or geography, if not on some scary occasions, against the ungodly. When it comes to the romance novel, Rodale provides the offhand observation: “There are obstacles and dark moments when all seems lost before ending happily”.

Regis suggests that a romance has eight such narrative elements, which can appear in any order (though her choice of sequence is suggestive). They are: society defined (what the heroine will have to confront); the meeting (in film, the cute meet); the barrier (the reason, internal or external, why the hero and heroine can’t get together); the attraction (what keeps the hero and heroine together long enough to overcome the barrier); the declaration; the point of ritual death (where all seems lost); the recognition (a something that will help the hero and heroine overcome the barrier); and the actual betrothal (getting together for now, if not forever). She adds three frequent, but not necessary, elements of a wedding festival of some sort; the exile of a scapegoat character; and the conversion of a bad or antagonistic character. Pamela, of course, has all eight elements.

Regis suggests that a romance has eight such narrative elements, which can appear in any order (though her choice of sequence is suggestive). They are: society defined (what the heroine will have to confront); the meeting (in film, the cute meet); the barrier (the reason, internal or external, why the hero and heroine can’t get together); the attraction (what keeps the hero and heroine together long enough to overcome the barrier); the declaration; the point of ritual death (where all seems lost); the recognition (a something that will help the hero and heroine overcome the barrier); and the actual betrothal (getting together for now, if not forever). She adds three frequent, but not necessary, elements of a wedding festival of some sort; the exile of a scapegoat character; and the conversion of a bad or antagonistic character. Pamela, of course, has all eight elements.

Mernit, one of the few men to write Harlequin romances, suggests that there are seven beats and a clear sequence. They are: the set-up (what is wrong with each character, what needs to be fixed, how each balances or complements the other); the catalyst (or the meeting); the first turning point (what the barrier to love is, roughly at the one quarter point); the mid-point hook (what situation or circumstance binds them together); the second turning point (where the main protagonist – hero or heroine – is faced with choosing either lover or some other goal; roughly the three-quarter point); crises climax (when one or the other, if not both, seem lost); and resolution (or joyful defeat – the couple get together, marriage is often implicit in contemporary romance).

As for the actual hero and heroine of romance novels, the RNA observes that most readers like ones they can identify with or has to struggle against adversity or overcome great odds. The most popular romantic tropes are friends becoming lovers; fate connecting soul mates; and a second chance at love (with older heroes and heroines). Rodale points out that the characters should be realistic and recognizable and that “what matters is if the emotions ring true”.

As for the actual hero and heroine of romance novels, the RNA observes that most readers like ones they can identify with or has to struggle against adversity or overcome great odds. The most popular romantic tropes are friends becoming lovers; fate connecting soul mates; and a second chance at love (with older heroes and heroines). Rodale points out that the characters should be realistic and recognizable and that “what matters is if the emotions ring true”.

This doesn’t mean that the characters are nuanced in the same sense as mainstream fiction. The four genre archetypes may not be as obvious as they were a century ago, but they remain. The character who seems to be good and is good; the character who seems to be good, but is bad; the character who seems to be bad, but is good; and the character who seems to be bad and is bad. In the “old days” the bulk of genre characters were at the ends of that spectrum; these days the bulk is in the middle.

Heroines tend to be attractive, confident, and ambitious. Rodale surveyed readers of romance novels to find out what characters were most valued in a heroine. Intelligence, a sense of humor, and independence topped the list. She also found out that readers like heroines who “do something”, that is, have a job or profession. According to the surveys, some 53% feel that such heroines make excellent role models.

Regis suggests that “We imagine heroines go on even if we don’t see them do so”. Interestingly, in MC romance novels, we often do see the hero and heroine go on. The books are often written as a series. A club member who is a supporting character in one book is the hero in the second and we find out what happened after the Happily Ever After (HEA, in the world of romance novels) when he and the heroine are supporting characters in a third. Another exception is the Amelia Peabody series by Elizabeth Peters (Barbara Mertz). The first book, Crocodile on the Sandbank, is a romance novel, but in the rest of the series, Peabody functions as something between a detective and a dea ex machina. The mix of fact and fiction with flights of fancy is only matched by George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman series. If you like one, you will probably like the other. Those who have problems with the deliberately unbelievable tale may wish to skip both.

Regis suggests that “We imagine heroines go on even if we don’t see them do so”. Interestingly, in MC romance novels, we often do see the hero and heroine go on. The books are often written as a series. A club member who is a supporting character in one book is the hero in the second and we find out what happened after the Happily Ever After (HEA, in the world of romance novels) when he and the heroine are supporting characters in a third. Another exception is the Amelia Peabody series by Elizabeth Peters (Barbara Mertz). The first book, Crocodile on the Sandbank, is a romance novel, but in the rest of the series, Peabody functions as something between a detective and a dea ex machina. The mix of fact and fiction with flights of fancy is only matched by George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman series. If you like one, you will probably like the other. Those who have problems with the deliberately unbelievable tale may wish to skip both.

While the heroines may be intelligent and independent, the heroes are made of different cloth. They are classic alpha males, even if the dukes and sheiks of a hundred years ago have been replaces by billionaires and bad boys. Dominant, confident, and hyper-masculine, they have it all and get the girl, according to Rodale. More important, they tend to nurture the heroine, though the line between nurturing and controlling may be a fine one. Rodale adds that the hero’s “triumph is not getting laid, but in getting her off”. However, “that bad boy will soon be reformed. And he will like it”.

Although, perhaps the “heroine doesn’t want to tame the bad boy so much as ride off into the sunset with him”. Rodale quotes a reader who claims that the bad-boy lets women release their inner “bad-ass chick[s]”. Little wonder Fry noted, “From what I’ve read the heroines tend to be strong women who can go toe to toe with their alpha, MC heroes.”

The results of Rodale’s own surveys – she ran about ten of them – suggest there’s more than just that. What readers look for in a hero is a sense of humor, honesty and integrity, and kindness; “flawed, but a good heart”. Intelligence, it seems, is more valued in a heroine than in a hero.

In Random House’s Motorcycle Clubs in Romance Novels. Let’s Ride, MC romance novelist Carla Swafford asked, “Who doesn’t love a bad boy? I’m sure sexy Charlie Hunnam’s Jax Teller helped the demand along”. She went on to point out that the biker also fits the description of an anti-hero.

In Random House’s Motorcycle Clubs in Romance Novels. Let’s Ride, MC romance novelist Carla Swafford asked, “Who doesn’t love a bad boy? I’m sure sexy Charlie Hunnam’s Jax Teller helped the demand along”. She went on to point out that the biker also fits the description of an anti-hero.

Megan Crane added in that round-table “about motorcycle-man-candy” that “Deep down, bikers are usually deeply protective. If you get into his heart, he’ll defend you and protect you with every last bit of his soul – and his fists.”

In a way, the MC bad boy echoes what I noted in The Rhythm and the Ride (issue 194 Summer 2016) about the biker in a motorcycle song. He is “some sort of working-class Byronic bad boy, whether from some sort of unstated tragedy or post-Jungian journey. There’s a sense of the rider having gone past the redline and went somewhere no one is supposed to go; but unlike so many who did, managed to get back somehow, damaged, if not damned”. The difference is telling. In the songs, bikers can be losers, goofballs, or even just regular guys. In the novels, they have to be strong men with dark secrets.

Regis notes that “this kind of romantic hero is himself a barrier” and that the sentimental hero, one who has felt some great hurt, will be healed. Not only that, if Rodale is right, he will like it.

The appeal of the MC biker goes beyond the biker himself. Swafford said at the round-table, “I believe it’s the contradictions. They do all kinds of illegal things but they look out for each other. They even have a strange sense of honor.”

Crane added, “I love the specific outlaw component of the biker world. I love these dangerous men who any smart girl would see as a threat, but who live by codes of honor and love for their brothers and their club. We know the biker loves his club and his brothers, so we know he COULD love us too, while still being so wild and free and outside the bounds of regular society.”

Violetta Rand, the third round-table participant, pointed out, “It has everything to do with vigilante or frontier justice. Bikers have a code they live by. If people violate it, punishment follows. I think readers appreciate that type of swift action. Sometimes it takes a biker to step in where the law has failed to act.”

For the writers, the milieu may be as exciting as the heroes they create, “The almost tribal nature of MC culture gives me the freedom to mash a story with all the elements of a historical into a contemporary setting,” Wylde said.

Wylde, who prides herself on her research, explained, “I didn’t grow up knowing a lot of bikers, so when I stared learning about MC culture I was fascinated. I had a lot of preconceptions about their lifestyle (probably very similar to assumptions about romance readers and writers, actually). The more research I did, the more I realized that my stereotypes were wrong and before long I was interviewing bikers to learn how clubs really work in the real world. One day I woke up with a story idea, wrote it, and my entire life changed.” She counts real MC members among her readers. Male and female.

While the level of research and verisimilitude varies from writer to writer, overall it’s quite high, much higher than say the research male pulp writers did for biker gang men’s adventure novels in the 60s and 70s. Most of the writers of MC romance novels don’t ride or, like Crane, just ride pillion. Rand, on the other hand, raced semipro for three years and has a taste for classic bikes.

The writers whose works are most often included in lists of Motorcycle Club Romance Novels include, in addition to Wylde, Kristen Ashley, Janice Bagley, Tillie Cole, Nicole Jacquelyn, Bella Jewel, Kim Jones, Nina Levine, Madeline Sheehan, and Crystal Spears. Wylde and Ashley seem to vie for top place on these lists, with Sheehan trailing close behind.

The writers whose works are most often included in lists of Motorcycle Club Romance Novels include, in addition to Wylde, Kristen Ashley, Janice Bagley, Tillie Cole, Nicole Jacquelyn, Bella Jewel, Kim Jones, Nina Levine, Madeline Sheehan, and Crystal Spears. Wylde and Ashley seem to vie for top place on these lists, with Sheehan trailing close behind.

All those writers – and dozens more – have incredibly loyal and engaged fan bases. Wylde’s user group has some 5,000 members. A casual query she posted on my behalf garnered about 120 responses within 24 hours. Goodreads’s fan group, Bike Book Babes, has only 1,600 members, but the degree of engagement is no less. Reviews, recommendations, and shirtless photos of Hunnam abound. Some of the posts in such groups can be more than a bit raunchy and X-rated. Girls’ locker room comments it seems are no better than the boys’.

Critical reception for the romance novel has not been as warm and supportive. Some of this is consistent with how other genres are or have been treated. Westerns are just “horse operas”. “Ninety percent of Science Fiction is junk”. Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd? “One of the least pleasant parts of writing romance is the way that people occasionally react with snide or condescending assumptions,” Wylde said. Romance novels are damned because they are romance novels Regis notes succinctly. Rodale points out that snide comments and superior complaints about those who read for pleasure were already common by the Eighteenth Century. The basic arguments about the purpose of art (or in this case literature) go back to the ancient Greeks at least. We need only to read The Poetics. Rodale learned from her surveys “that there is undeniably a negative perception of the genre and its readers and romance fans were aware of it.” Approximately, two-thirds felt romance novels don’t get the respect they deserve and just over half hid their interest in romance novels.

Among the typical charges against romance novels are that they have no suspense since the reader knows that the books end HEA. So do whodunits in general and cozies in particular. The mystery is solved, chaos has been laid to rest, and all’s right with the world. That’s just as predictable and just as happy. To be fair, mysteries get more respect than romance novels – or is that they get a lot less disrespect? Another charge is that romance novels mislead women into having unrealistic expectations about life and love. This presupposes that women readers can’t tell the difference between reality and fantasy. Not in my experience, but we’ll get back to this point in a moment.

Among the typical charges against romance novels are that they have no suspense since the reader knows that the books end HEA. So do whodunits in general and cozies in particular. The mystery is solved, chaos has been laid to rest, and all’s right with the world. That’s just as predictable and just as happy. To be fair, mysteries get more respect than romance novels – or is that they get a lot less disrespect? Another charge is that romance novels mislead women into having unrealistic expectations about life and love. This presupposes that women readers can’t tell the difference between reality and fantasy. Not in my experience, but we’ll get back to this point in a moment.

The more serious critiques come from the Marxist and some Feminist schools. Essentially they treat romance novels as propaganda to indoctrinate women into subservient roles through marriage. It is therefore a sinister distraction from political action or self-actualization (itself seen as a distraction from political action by some Marxists). Given the usual thread of Marxist literary theory, we note the absence of comments about imperialism and colonialism despite the fact that most romance novels are written by authors from English-speaking countries and both consciously and unconsciously reflect an “Anglo-Saxon” point of view. But then again Edward Said did have a few sharp comments about Jane Austen.

Not all Feminist critics buy into that analysis. For these theorists, romance novels are not oppressive, but subversive. Romance novels encourage women to fight inequality and set high expectations (with some examples of how to achieve those expectations). The heroine calls the shots and makes the choices. She tames the hero, takes his power and privilege, and becomes an equal partner. And he will like it.

Rodale notes that “By creating stories with an intense focus on a heroine – her choices, her pleasures, her independence, and her rewards – romance novels promoted radical ideas of what a woman could do with her life and inspired women to try to make that dream a reality.” Her surveys back up her observation. She found that some 62% of people who read romance novels felt they empowered women and 60% of the readers considered themselves Feminists.

Rodale, in her well-researched, well-argued, and survey-mad book makes the case that is in part why romance novels are dismissed when they’re not ignored altogether. She claims that “dismissing books as unrealistic is a way to lower expectations for relationships.” Since romance novels are the most popular books by women, for women, and about women, not reviewing “books that women read is another way of making women invisible.” She adds, “[I]t silences voices, erases an audience, sends the message that women’s stories don’t matter”. Reviews start a serious conversation about the books or themes or genres being discussed.

Sadly, much the same is true for motorcycle adventure travel books. Reviews are non-existent, reprinted or rewritten press releases, or someone babbling on about how great his or her friend’s book is. (It may well be, but the relationship invalidates the review on the grounds of conflict of interest.)

Oh, and, “Regarding bikers who aren’t part of MCs, I would say readers like them as heroes no matter what. It’s a sexy, positive thing. There are many romance books that have biker heroes, but they just aren’t a separate defined subgenre the way that MC books are. I’m not sure why – probably because the characters and stories are so diverse that they defy categorization beyond “contemporary” in general,” Wylde said. “As a romance writer, it’s rarely wrong to throw in a biker.”

Jonathan Boorstein

You can see more of Jonathan’s book reviews here.

Great article. I read most of these authors. I did notice you mentioned a Janice Bagley but I believe you meant Jamie Begley.

Thank you. It’s amazing how popular the article has turned out to be. And yes, you are correct, It should have been Jamie Begley. — Jonathan Boorstein

Interesting but I’m waiting for the second part of the article. You’ve got a neat overview of how the romance genre works in general but I’m waiting (breathlessly, blushing) for how things work out for the heroine in a specially biker-oriented story, what HAE might actually mean.

After all in real life if a lady gets involved with a biker, she’ll be lucky to get his full attention. She’ll be sharing his life with his bike or bikes. If he’s an MC type, she’ll be sharing him with his ‘brothers’ as well, and that MC lifestyle can be quite time-consuming, demanding regular runs away and long hours down at the clubhouse.

Also you must be aware that among bikers there are endless jokes and memes on the subject of either getting away from women, or that the bike matters more than she does. At most bike events, you can buy a T shirt with ‘if you can read this, the bitch fell off’ written on the back. Or cards/jokes/plates/fridge magnets on the theme of being asked to choose between her and the bike, and taking the bike. Of course this is comedy, but there may be a nugget of truth. I can’t think of many other activity groups who make such a play of getting away from the wife/girlfriend. Golfers, perhaps. Or maybe fishermen. If i was a female, I might find this whole atmosphere a barrier to romance.

So in the Happy Ever After of biker romances, what happens? 1) He gives up the bike and joins her as a respectable person? 2) He dies in a bike crash and she mourns him forever? 2) She joins him on the pillion and they ride off into the sunset? 3) She gets welcomed as a (subsidiary) member of the gang? (Good luck with that.) 4) She gets a bike of her own and they ride together? I’d like to know which outcome the novels favour.

There is one true outcome that I have come across in real life. Rebellious young girl gets involved with bike gang. Drops out of school/college. Hooks up with biker. After a few years, gets bored with the limitations of the biker lifestyle, and realises she can do better. However the biker episode has given her qualities of energy and determination. So when she goes back to school, later, she cuts through the competition. And that explains why the history professor, or senior hospital doctor, or managing director, has tats, a leather jacket and a bike in the car park. Mind you that’s a longer story.

In my book “The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love” (Belhue Press, 2015) I present once again the following, old tried-and-true quote: “Every girl is looking for a bad boy who’ll be good just for her, and every boy is looking for a good girl who’ll be bad just for him.”

I think that describes biker romance in nutshell.