Of Bikers and Baiku

Boy on a motorcycle

Riding where the road leads

Comes to a fork

That banal bit of verse is known as baiku, or motorcycle haiku. Baiku is but one example of the growing sub-genre of motorcycle poetry. For better or for worse, baiku has even generated a web page dedicated to such examples.

What, you ask, is motorcycle poetry? Does it really exist? Is it any good?

It came to the attention of The Rider’s Digest thanks to an over-active press agent. The agent touted Ryan J-W Smith, who, in addition to being both a motorcyclist and a writer/director, has produced 500 Shakespearean Sonnets: the diary of a poetic quest for truth. (Shakespeare himself wrote a mere 154. Or as another poet, Robert Browning, said in Andrea del Sarto: “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for?”) Smith has continued the project by blogging sonnets in his Sonnet Blog. At least two involve motorcycling. One, Sonnet 626, is an ode to his Honda:

The bliss of my contentment I shall write,

For she is joy and wonder, through and through;

Not only is she moving to my sight,

Her energy, my speed-head doth subdue.

Acceleration like a bullet shot:

I slip a little backwards as she pulls;

As I hold on, I know that I could not

Be ever from her side – we’re raging bulls!

Together, my machine and I, are one;

She teaches, and I listen as she sings;

Her notes are honey-coated loving fun:

I cannot here express the thrill she brings,

I seek excuses to go near and far:

I love my ninety-nine – my VFR.

In terms of rhyme, meter, and volta (the last two lines or couplet) it is as advertised, a Shakespearean sonnet. However, it is hardly Shakespearean in the popular sense of the word. It’s light verse. The volta is more a punch line than a summation; leaving more a sense of a smile than of the sublime. It even lacks the shallow existentialism of the opening haiku. But the sonnet works on its own terms. The typical motorcyclist will relate to what Ryan Smith writes.

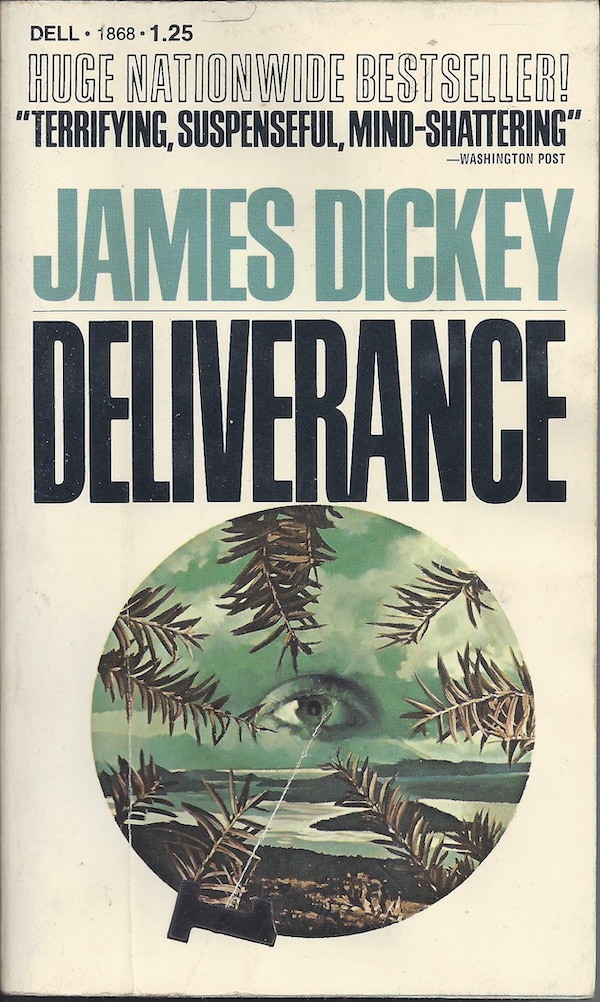

Of course, great poets also produce their fair share of light verse. Some even produce motorcycle poetry. American Poet Laureate James Dickey, best known for his novel, Deliverance, writes in Cherrylog Road:

And I to my motorcycle

Parked like the soul of the junkyard

Restored, a bicycle fleshed

With power, and tore off

Up Highway 106, continually

Drunk on the wind in my mouth,

Wringing the handlebar for speed,

Wild to be wreckage forever.

I’m not an expert in Dickey’s poetry, but motorcycles and motorcycling seem to recur as both theme and motif. May Day sermon to the women of Filmer County by a lady preacher leaving the Baptist Church includes such passages as:

Gnats in the air they boil recombine go mad with striving

To form the face of her lover, as when he lay at Nickajack Creek

With her by his motorcycle looming face trembling with exhaust

Fumes humming insanely

And

she hears him creaking

His saddle dead-engined she conjures one foot whole from the ground-

fog to climb him behind he stands up stomps catches roars

Blasts the leaves from a blinding twig wheels they blaze up

Together she breathing to match him her hands on his warm belly

His hard blood renewing like a snake O now now as he twists

His wrist, and takes off with their bodies:

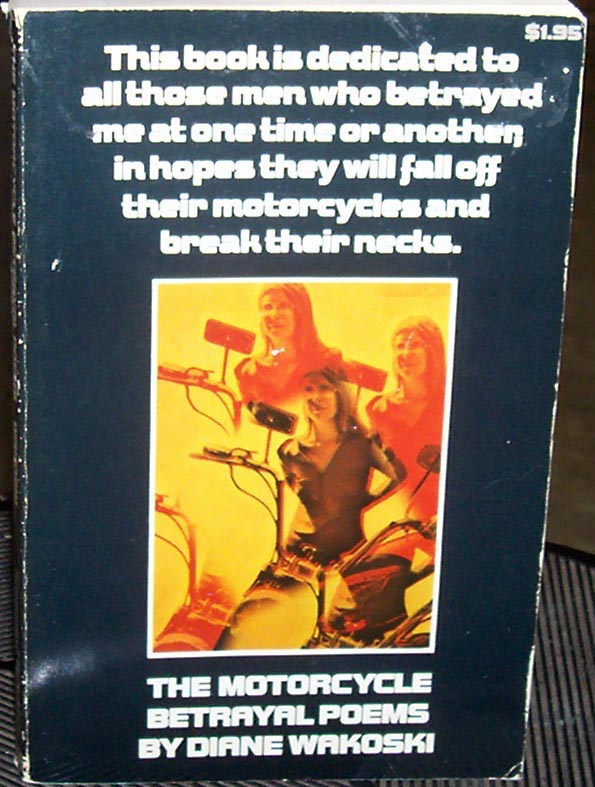

Diane Wakoski also plays with such themes and motifs. In Uneasy Rider she says:

You are more beautiful than any Harley-Davidson

She is the rain,

Waits in it for you,

Finds blood spotting her legs

From the long ride.

And she continues elsewhere in The Motorcycle Betrayal Poems:

Just being so joyfully alive

Just letting the blood takes it own course

In intact vessels

In veins…

– the motorcyclist riding along the highway

Independent

Alone

She dedicates the poem cycle to “all those men who betrayed me at one time or another, in hopes they will fall off their motorcycles and break their necks”, which suggests her relationships to motorcycles and motorcyclists is – how to put this politely? – complicated.

A Real Motorcycle by Erin Moure includes:

Like running the motorcycle full-tilt into the hay bales.

What is the motorcycle doing in the poem

A. said.

It’s an image, E. said back.

It’s a crash in the head, she said.

It’s a real motorcycle.

And later Moure writes:

Or the flat bottom of the former sea

I grew up on,

Running the motorcycle into the round

bay bales.

Hay grass poking the skin.

The back wet.

Tom Andrews, a winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, serves up a different point of view in the creepily titled Hemophiliac’s Motorcycle:

May the Lord Jesus Christ bless the hemophiliac’s motorcycle, the

smell of knobby tires,

Bel-Ray oil mixed with gasoline, new brake and clutch cables and

handlebar grips,

the whole bike smothered in WD40 (to prevent rust, and to make

the bike shine),

And continues some lines later with:

the bike flying sideways off a jump like a ramp, the rider leaning his

whole body into a left-hand corner

As well as:

a first moto holeshot and wire-to-wire win, a miraculously benign

sideswipe early on in the second moto

bending the handlebars and front brake lever before the possessed

rocketing up through the pack.

Of course, most motorcycle poetry is not at that level. It’s more in line with Smith, our sonneteer. It focuses on motorcycles, motorcycling, motorcycle clubs – outlaw and otherwise, road trips and road kill, urban bikers and urban legends. The tone is “folksy” and the point of view, working class, some examples taking the ugly resentment form of inverse snobbery.

Bruce “Bulldog” Dowling’s Roadhouse Blues takes a typical biker moment – too long in the saddle – in a traditional rhyme and meter.

It looms in the distance, it calls you so clear,

It speaks to you softly so no one can hear,

On the side it stands, jealous, of the roads strong allure,

It offers you solace, redemption, a cure

For all that is ailing, each chronic attack,

The cramp in your foot, the pain in your back.

That old hardtail’s making it easy to choose,

The song of the sirens, those old Roadhouse Blues.

Larger and brighter, its lights draw you hard,

Your fatigue it is winning, you play your trump card.

The brakes are your tonic, the balm that you crave,

As they aid your escape: your reprieve from the grave.

In minutes the barstool your confession will hear,

Your act of contrition, an annointment of beer,

That pours from the tap of your own private brew,

That lullabye liquid, those old Roadhouse Blues.

While not a true Blues, we all know what the narrator is talking about and relate to that “predicament”. How the narrator got home (or didn’t) after the glass or two may well be inspiration for a more traditional Blues.

In Unlike Rider, barthibbard takes a look at the choice between riding and mousing with similar good humor.

Mousing through the cheerful haze,

or pistons hot- revving phase.

Wistful quests within the cloud,

I suggest exhaust pipes loud….

Unknown minds control your fate,

Of Facebook I do hesitate!

Liking you without those clicks-

When gasoline with air doth mix.

And Blaze makes light of a Night Run:

there’s something in the air…that scent…

you know the one – it drives you crazy –

makes you crank that throttle hard

too far too long…you pray no deer

from there to here – – – and then

you taste that thin eyed lost soul grin

lean on in

and laid out

let her fly

Rather like cowboy poetry, motorcycle poetry reflects a romanticized view of what is presented as an American lifestyle. There are: the loneliness of the solo rider; the camaraderie of riding with friends or in a group; motorcycle maintenance; the freedom of the road; outlaw clubs; highway traffic and accidents; biker values and practices; and the obvious observations common to most bikers. Some are about moments and memories; others are tall tales and folk tales.

While cowboy poetry has its fill of tales, it is longer, living tradition and its forms go back to when literacy was less common and the Western lifestyle was actually made up of ranch work and those who did it. Rhymes and meters were used to aid memory. The landscape of the North American west is as important as cowboy values and ironic observations about ways and means of modernity.

Motorcycle poetry is more recent and grew out of the lifestyle of the post-World-War-II American biker clubs. Hunter S. Thompson both practiced and popularized motorcycle poetry. As Shirley Dent observed in The Guardian (16 November 2007) in a blog titled Motorcycles and the art of poetic utterance: “the motorbike and the poem are creatures akin. They straddle physical and intellectual sense – even though you feel physics working through you when you are on a bike, being on a bike is not about succumbing to the physical or losing all sense. There is precise science in the recklessness of both riding a bike and writing a poem”. And both she points out “take you out of yourself”.

Smith’s sonnet fulfils much of that basic criteria, as do the pieces by the motorcycle poets themselves. Interestingly the criteria could be applied to motorcycle song lyrics as well. Leiber and Stoller’s mid-1950s hit Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots is certainly one example:

Then he took off like the Devil and there was fire in his eyes!

He said “I’ll go a thousand miles before the sun can rise.”

But he hit a screamin’ diesel that was California-bound

And when they cleared the wreckage, all they found

Was his black denim trousers and motorcycle boots

And a black leather jacket with an eagle on the back

But they couldn’t find the ‘cicle that took off like a gun

And they never found the terror of Highway One Oh One

Bill “Uglicoyote” Davis, one of the better motorcycle poets, and clearly influenced by such lyrics, wrote in Riding Through The Fire:

So he went ridin’ through fire

He rode through the smoke of Hell

He just crossed the Jocko River

He had to make it to Kalispell.

She heard about it the next morning

He’d run a road block, the announcer said

On a closed highway he’d lost control

In the flames they found him dead.

She wondered why he made that run

What caused him to take that ride?

Her husband didn’t see the tear that fell

With the name of the man who had died.

He’s still ridin’ through that fire

He’s still ridin’ through the smoke of Hell

Around him all is burning

And a woman weeps in Kalispell

Davis’s poems appear both online and in print. In a post on The Hard Rider blog, he writes: “Do you even know it exists. There are several Road Poets out and about. You can check in to my poetry blog, Songs of the Open Road to read some of my work. I’ve posted my most recent words below. You might also want to check out Road Scribes of America: A fellowship of ~ the Road ~ the Wind ~ the Pen of which I am a member.”

Motorcycle poetry sites go from the general to the specific. Some even provide guidelines to help the aspiring rider writer. The motorcycle haiku site not only gives advice: “Haiku is a three line unrhymed verse with the first line containing 5 syllables, the second line containing 7 syllables and the last line containing 5 syllables. Sometimes the verse has a seasonal theme”; but also provides examples:

Summer calls to me

Come ride your motorcycle

Live without your cage

Parenthetically, haiku usually (not “sometimes”) has a seasonal theme or reference (to be precise) as well as a pivot upon which the first half of the haiku turns to the second. While haiku written in English does have to have three lines, it is not restricted to 17 syllables arranged 5-7-5. It would be perfectly acceptable to write:

Baja

Dia de los Muertos

Jolly Roger on the gas tank

in which Dia de los Muertos is both the pivot and the seasonal reference.

Printed anthologies while still uncommon are available. “Little did I know that well over thirty five years ago when I scribed my first motorcycle poem, I would be here today a part of the Bikerpoetry movement and asked to write the afterword for Verse And Steel. I can remember back in the day when Bikerpoets were lucky if they received one or two hard copy publishings a year and now with the support of monthly motorcycle magazines and newspapers, as well as the many internet resources available, opportunities abound for the arts and artists of the biker lifestyle,” writes Sorez the scribe in Verse and steel. “Way back when, I had no idea that there were other like minded individuals out the riding and writing their way down the road and into literary history.”

Nor is that the only volume. Yoga and the Art of Motorcycle Poetry was sold in City Lights Bookstore, owned and operated by the great beat poet, Lawrence Ferlinghetti. While not an actual endorsement, the shop is known to be fussy about the titles it stocks.

The biker poetry community also includes Martin Jack Rosenblum, a former official historian for The Harley-Davidson Motor Company, and QBall, a frequent contributor to the Vtwinbiker site. And to be fair probably most riders who want to be writers have tried their hands at one form of verse or another. Self-disclosure: I snuck two of my haiku into this piece.

Perhaps inevitably the term “motorcycle poet” is reserved for those who write lyrics or light verse almost exclusively about the riding life. If the work is serious, then it is by a poet who happens to write about motorcycle, among many other things (or the motorcycle is a metaphor for many other things). One can’t quite imagine Dickey calling himself a motorcycle poet despite his careful cultivation of a macho, bad-boy image.

Others are more open to the fun of having it both ways, of blurring the identities of motorcycle poet and poet who writes about motorcycles. Frederick Seidel is quite blunt that he writes prose and poetry about motorcycles, his suggestively named book of verse, Going Fast, certainly covers more than just motorcycles (Poem does, for example). Dent seems fond of his line “I am the Ducati of desire/144.1 horsepower at the rear wheel”. Ducatisti Seidel may be, he nevertheless ended an op-ed piece he wrote for The New York Times entitled Is the Era of the Motorcycle Over?, with the crypto volta:

Better to be out in the air astride

Just about any motorcycle alive!

But perhaps the last word should be left to Davis, as a sort of coda if not volta. As a “real” motorcycle poet, he not only revels in that identity, but also wrote:

Can you tell truth about the joy

that sometimes rises deep inside

or about the hard and tough times

that you’ve had along your ride.

Road Poet, tell the whole truth,

don’t hold back, spill your gut.

As you ride your roads and write your odes,

tell the truth and nothing but.

Jonathan Boorstein

This article first appeared in issue 173 of The Rider’s Digest in December 2012